JF Ptak Science Books LLC Post 207

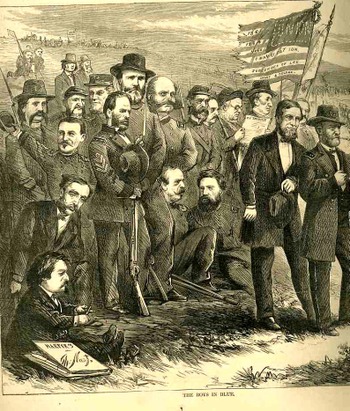

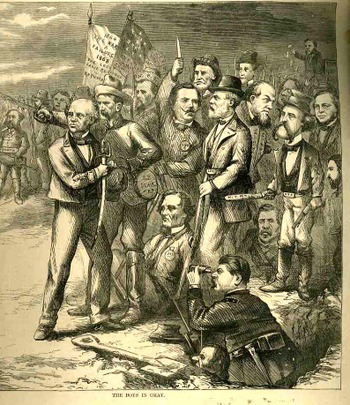

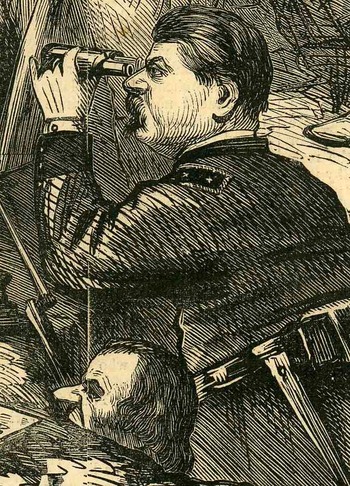

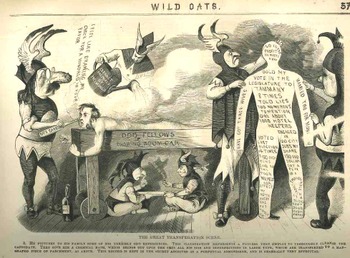

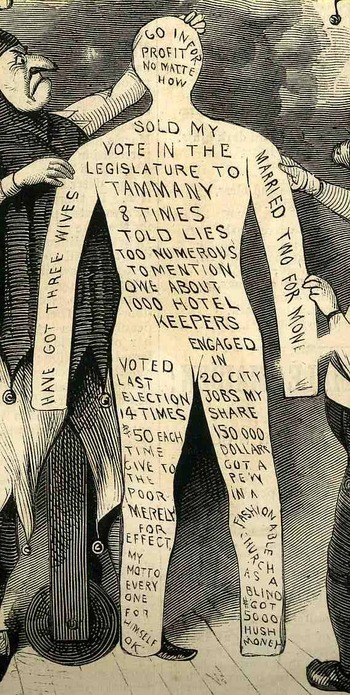

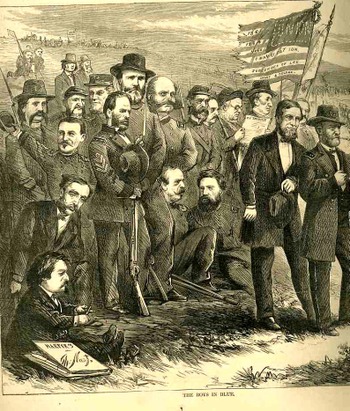

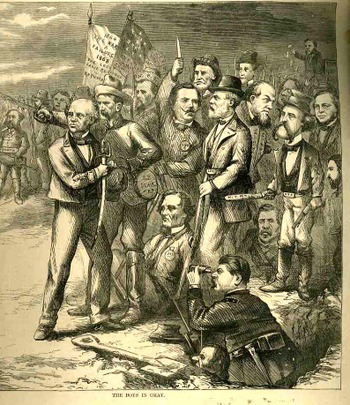

It is in this complicated, otherwise-involved political graphic statement that we can find one of the great, quiet put-downs in the history of 19th century political cartooning. The image belongs to Thomas Nast, a remarkable social artist, who worked very heavily between 1860-1885, producing about 3000 pieces similar to this in level of involvement and complexity—a truly remarkable, verb-laden, Herculean output. Very little escaped his microscopic/telescopic vision, capturing interests in the big and small, and also along the way creating our popularly-known images of Santa Claus, the republican elephant, the Democratic donkey, and the Tammany tiger; he also helped to re-elect Lincoln in 1864, destroyed Boss Tweed, and challenged the embarrassing mores on public education, the treatment of African Americans, rights of women, and more. His observations were generally very insightful, mostly cutting, occasionally vicious, but spot-on. He must have lived and breathed his art, because by the time he was 50 he was pretty much done, artistically, after an already 35-year career; he was dead at 62, busted and far from home.

In this drawing Nast draws the bead on the 1868 presidential election—the first since the end of the War—between the republican U.S. Grant and Democrat Horatio Seymour. Nast had no use for the democrats in general, finding them basically odious, and actually treasonous, and he lines the two parties up along the old lines of the Civil War, the Republicans as blue and the Dems as gray (and it is generally true to say that the Democratic Party was closely aligned with the South through this period of time). In spite of the fact that Seymour (seen here at the head of the jumble of graycoats with the blood-dripping sword) was from Ohio didn’t matter—he was seen by Nast as a continued sympathizer and a wreck on the best thing to do for the South following the war.

The larger issue for Nast (who pictures himself in the image with the Blues at the lower left, with a steely gaze, sharpening his pencil) goes back to the election of 1864, when Seymour ran as the vice president in the )democrat) presidential campaign of Gen. George McClellan, who is, ultimately, the object of the great putdown. Nast’s distaste/hate goes far back with the little General, who was at one time not only the commander of the Army of the Potomac but was also Commanding General. McClellan arrived to the war as a hero of great celebrity, which was wasted in about a year. As a general in command of the North’s leading army, McClellan suffered as a result of his own meticulous, chess board, keep-it-on-a-shelf strategy of carefully considered inaction; he killed himself, suffocated by his alphabet of cautions and a little bit of Confederate diversionary theatrics. George never had enough men to suit his attacking the skirting Confederate armies, almost always grossly overestimating the strength of his opponent. He just wouldn’t go. (Lincoln famously remarked on McClellan: “He has got the Slows!”.) McClellan was an intelligent and sharp, but he was god-awful immobile and immovable.

But what really got to Nast was McClellan’s campaign for the

presidency in 1864 against his former Command-in-Chief. Once he was finally, thankfully, relieved of

his command, McClellan found political interests, winding up as the Democratic contender

for the presidency. Early on in his

campaign McClelland adopted a policy—which was subsequently scrubbed but not

forgotten—calling for ending the war and negotiating a peace and settlement with

the Confederacy. Nast hated him for this

move. McClellan actually received 45% of

the popular vote running against our best-ever president and with the country

still at war (although he was obliterated in the electoral college 212 to

21). I have no idea, really, what

McClellan was thinking.

Now, getting back to the 1868 election. Again, the republicans and democrats were set

out on the battlefield and battledress of the just-finished war, blue and gray,

respectively. In blue we see US Grant

and Shuyler Colfax (his VP, standing just behind him), while in the crowd we

can find

Sherman,

Greeley, Burnside and a host of the other Union greats. On the opposite side is Seymour with the dripping sword with the

backing of his VP Francis Blair ; Jeff Davis

is sitting on the ground, Lee is otherwise occupied, and a host of other

Confederate icons stand wide and deep.

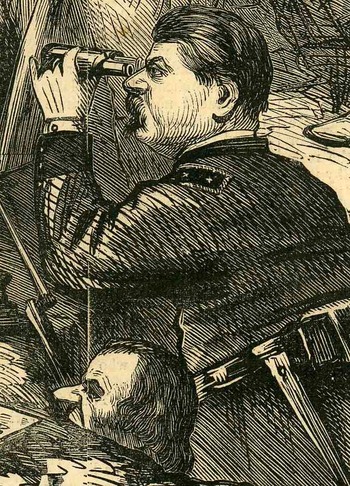

Nast again is looking with squinty eyes across the field,

where he has placed, mole-like, the Union General McClellan, emerging from his

hole, having dug his way over to the Other Side, and now observing the Unionwith a telescope. Such was Nast’s distaste for McClellan that he placed him, before all

others, on the opposing side, telling us that the man might as well have fought

with the South. We also see President Andrew

Johnson peering out of the hole at nostril level—Nast hated him too, finding

him a repellent appeaser who sold out the Lincoln

post-war policies. Grant wound up

winning the election by a slim popular vote margin with 53% (and this without

three of the Southern states being readmitted), but trounced Seymour 214-80 in the electoral college.

And so it was that Nast drew the battle lines for the

election, making it a north-south issue, and burying alive his reviled odd

couple of McClellan and Johnson, finding them traitors in the end, in an image

that could be understood by even the illiterate newspaper reader.

"The lunatic , the lover and the poet,

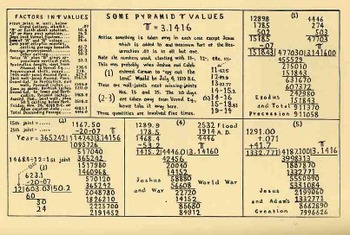

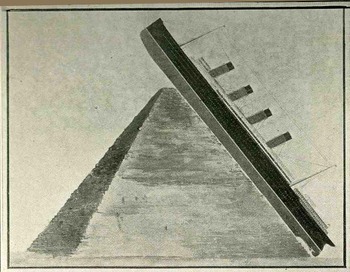

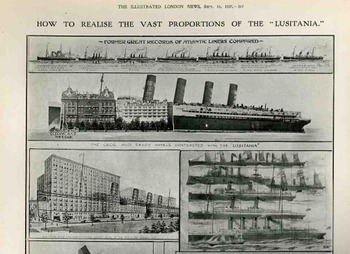

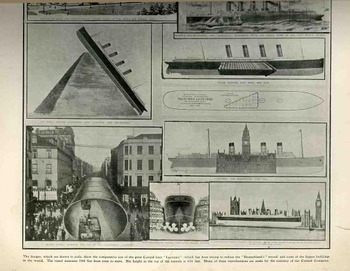

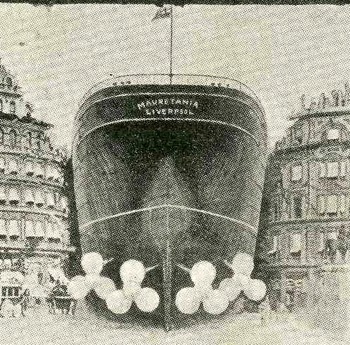

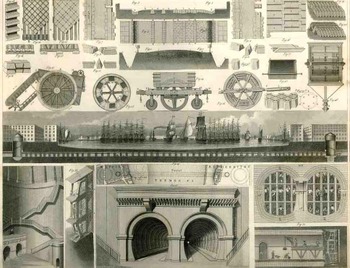

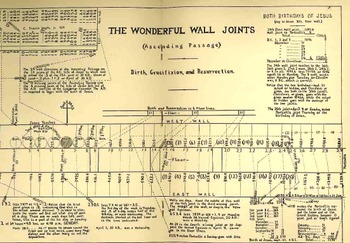

"The lunatic , the lover and the poet, But Mr. Pickett did evidently assemble ALLOT of data and drawings and plans and renderings of the pyramids in the course of looking for the secret strings which would alter the known into the secret and unknown.

But Mr. Pickett did evidently assemble ALLOT of data and drawings and plans and renderings of the pyramids in the course of looking for the secret strings which would alter the known into the secret and unknown.