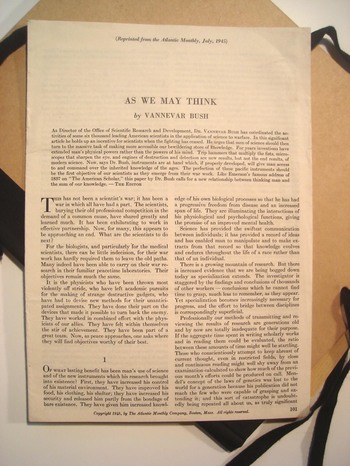

JF Ptak Science Books LLC Post 190 In the midst of running the American scientific war effort (As Director

of the Office of Scientific Research in charge of some 6000 scientists)

and in the middle of trying to figure out the best way of dealing with

the coming proliferation of atomic weapons, Vannevar Bush somehow found

the time to write what many consider to be the first scientific paper

on what would become the internet. The paper, "As We May Think"; was

published in the Atlantic Monthly in July 1945.

In the midst of running the American scientific war effort (As Director

of the Office of Scientific Research in charge of some 6000 scientists)

and in the middle of trying to figure out the best way of dealing with

the coming proliferation of atomic weapons, Vannevar Bush somehow found

the time to write what many consider to be the first scientific paper

on what would become the internet. The paper, "As We May Think"; was

published in the Atlantic Monthly in July 1945.

(It might be odd to look at it this way, but if you were a Nazi time traveler able to assassinate three people in the U.S. that would change the direction of the American effort in WWII, one would certainly be Roosevelt (who rose to the tasks of the Depression and the War with Lincolnian sustainability), and I'm not unconvinced that one f the other two might very well be Bush--he kept the scientific agenda on course, direct, and to the point, saving time, effort and lives. Its an interesting bit to think about....)

Bush was doing A LOT of thinking on the organization of thought in that year. I suspect that in trying to deal with the problems of the coming atomic arms race (beginning in the year before Trinity) and in trying to figure out how to distribute the knowledge-base that lead to the building of the bomb, that the idea of the MEMEX may very well have been the future consequence formed by his immediate concerns.

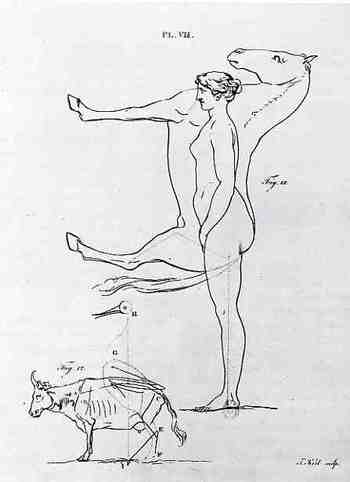

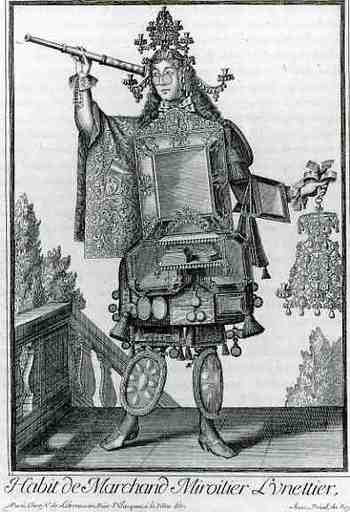

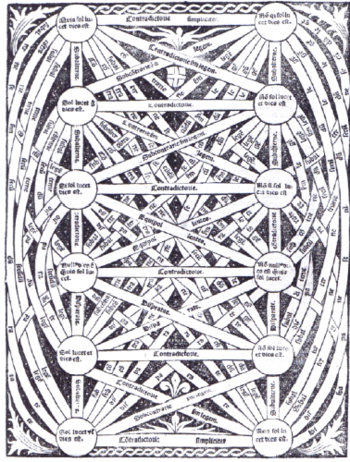

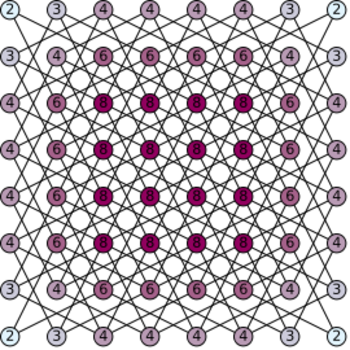

The MEMEX (Mechanical Aid to Memory) was Bush's breathtaking idea for a design for the organization of associative thought and memory. It was a mechanical “aid” to memory, building “trails” of associations of ideas. The MEMEX was another in the long line of art-of-memory attempts, from the ancients to the memory palaces and theaters of Raymond Lull and Francis Bacon and Athanasius Kircher and Giulio Camillo. What made this so appealing to the next generation of thinker on the distribution of information in the computer age was its ideas on making massive amounts of information obtainable; it was more about *thinking* about order and ability and access to information (in quantities unthinkable and by means unknowable) in 1945.

Looking at the future square in the face, Bush writes (on page eight of his short paper) with extraordinary perception:

"Wholly new forms of encyclopedias will appear, ready-made with a mesh of associative trails running through them, ready to be dropped into the memex and there amplified. The lawyer has at his touch the associated opinions and decisions of his whole experience, and of the experience of friends and authorities. The patent attorney has on call the millions of issued patents, with familiar trails to every point of his client's interest. The physician, puzzled by its patient's reactions, strikes the trail established in studying an earlier similar case, and runs rapidly through analogous case histories, with side references to the classics for the pertinent anatomy and histology. The chemist, struggling with the synthesis of an organic compound, has all the chemical literature before him in his laboratory, with trails following the analogies of compounds, and side trails to their physical and chemical behavior.

"The historian, with a vast chronological account of a people, parallels it with a skip trail which stops only at the salient items, and can follow at any time contemporary trails which lead him all over civilization at a particular epoch. There is a new profession of trail blazers, those who find delight in the task of establishing useful trails through the enormous mass of the common record. The inheritance from the master becomes, not only his additions to the world's record, but for his disciples the entire scaffolding by which they were erected."

Sounds pretty familiar, yes?

Some of the great internet developers who have recognized the importance of this paper by Bush include Doug Englebart, (who would write to Bush acknowledging the influence Bush's article had had on his own work. (Zachary, 267).); J.C.R. Liklider (Waldrop, 2000): and Ted Nelson (Internet pioneer and coiner of the term hypertext and know as "one of the most influential contrarians in the history of the information age." (Edwards, 1997)). And of course many, many others.

The full text of the paper "As We May Think" is below.